-

The European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) came into force on 1 January 2026, aiming to put a fair price on carbon for non-EU industrial products.

-

While initially praised, the policy has faced fierce criticism for being a protectionist measure that may violate WTO rules and unfairly penalise developing nations.

-

Research suggests that CBAM could significantly impact Africa’s economy, potentially reducing the continent’s GDP by $25 billion while raising an estimated £1.8 billion in annual revenue for the EU by 2030.

On 1 January 2026, the European Union’s (EU) Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) came into force, a measure described as putting a fair price on carbon and encouraging cleaner industrial production in non-EU countries by targeting carbon-intensive commodities.

CBAM was initially a welcome surprise. Many praised the EU’s initiative in using its economic power to encourage a greener global economy. The notion that the polluter pays surely aligns with what climate lobbyists have negotiated for.

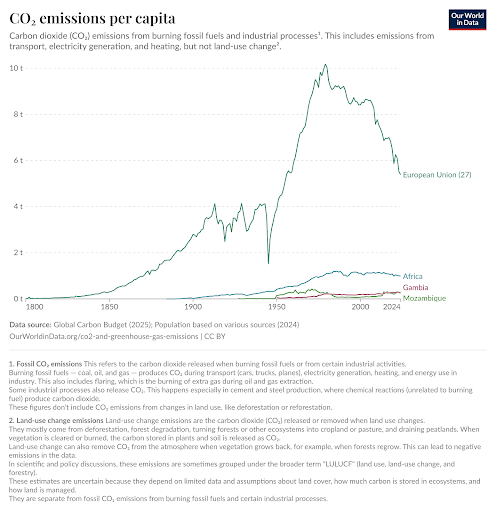

However, that is not the whole picture. Many of the nations labelled ‘polluters’, those lacking the investment to decarbonise industry, are among the world’s least developed countries. Those same nations emit roughly ten to fifty times less carbon per capita than the EU. Yet, under CBAM, they pay the EU. CBAM will raise an estimated £1.8 billion in annual revenue by 2030.

CBAM has faced stringent international criticism from those who accuse it of constituting a protectionist policy that violates World Trade Organization (WTO) rules. India’s finance minister, Nirmala Sitharaman, condoned the measure as a “repeat of colonialism.”

Yet, as the UK follows suit, announcing that its own CBAM will begin on January 1, 2027, who does CBAM make pay for the costs of climate change, and how did a protectionist economic policy become part of the UN’s climate change strategy?

Why have climate negotiations historically ignored trade ‘solutions’?

The 2025 United Nations (UN) Climate Change Conference, more commonly known as COP30, marked a crucial turning point in international climate negotiations, as trade became a major focus. Historically, trade has been absent from United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Conference of the Parties (COP) negotiations, remaining confined to WTO discussions – and for good reason.

Since the WTO’s establishment in 1994, the intersection of trade and climate has been the purview of the WTO’s dedicated Trade and Environment Committee, whose scope was expanded by the 2001 Doha Declaration.

The founding text of the UNFCCC, the UN Convention on Climate Change, signed in 1992, enshrines several key principles.

Perhaps the most important is the notion that countries should respond in accordance with “their common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities and their social and economic conditions,” a principle re-emphasised in the text on three occasions. Clause 3.1 extends the principle, reading: “Accordingly, the developed country Parties should take the lead in combating climate change and the adverse effects thereof.”

The basis for UN negotiations on climate change is that developed nations should do more than other nations to combat climate change.

In theory, the Convention does not exclude trade discussions; however, the equity enshrined in national decision-making at COP is essentially at odds with the principles of the international free market, leaving trade historically off the table in practice.

Clause 3.5 of the Convention addresses this, calling on Parties to promote an open international economic system that benefits all, stating that: “Measures taken to combat climate change, including unilateral ones, should not constitute a means of arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination or a disguised restriction on international trade.”

The Convention leaves no room for disagreement. When it comes to UN policy on climate change, trade can be important, but only if it benefits all. There is no basis to introduce trade policies that use protectionist instruments to tariff, levy, or tax our way out of climate change.

Protecting protectionism by appealing to emissions reduction

When the EU announced the CBAM, it was met with fierce accusations of “ESG colonialism,” as states warned that the policy’s protectionist nature constituted a disguised restriction on trade and a violation of WTO rules.

A 2022 report by the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) warned that four sets of WTO rules under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) could be invoked against the EU’s CBAM. However, there is an exemption under GATT Article XX(b) if the measure can identify legitimate public policy objectives necessary to protect human, animal, or plant life, and health.

The EU cited carbon emissions as a defence, claiming that they can pose a risk to EU citizens, irrespective of where they occur.

That means the EU can implement a traditionally illegal protectionist policy that essentially regulates emissions beyond its own borders if it can demonstrate that the trade policy contributes to reduced climate change risk for EU citizens.

What does COP have to do with it?

Since the EU’s CBAM policy announcement in December 2022, the EU and the UK, alongside other Western nations, have strong-armed trade into the COP agenda, despite its historical absence.

They have created a legal basis to present CBAM as a climate change solution, quieting international objections.

This occurred first at COP28 in November 2023, where there was an official “Trade Day,” with discussions, negotiations, and events held at the climate summit on the issue. This trade theme continued at COP29.

Ahead of the most recent COP30, held in Brazil, Western nations collaborated with the Brazilian presidency to launch the Integrated Forum on Climate Change and Trade (IFCCT), an independent advisory body to the WTO and UNFCCC, chaired by Brazil and a developed country partner.

Western nations mirrored this push at COP. At COP30, the presidency opened informal negotiations specifically on Unilateral Trade Measures (UTMs), actions taken by a single country or a group to restrict or influence trade, including CBAM.

UK and EU party delegates set the agenda. In a COP30 discussion, a UK delegate, mirroring language used by the EU and Australia, said: “The nexus between trade and climate is important” and “trade is a major source of CO2 emissions, and carbon leakage is a real threat. It must be tackled effectively,” language that repeatedly presented trade as inseparable from the climate negotiation process.

The consistent pressure from Western delegates paid off, securing trade’s place on the agenda. By the second week of the conference, UTMs, including CBAM, were among four key agenda items in the core agreement, the Global Mutirão (similar to the Paris Agreement 10 years earlier).

The final text finalised an agreement that called on the WTO, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), and the International Trade Centre (ITC) to collaborate with the UNFCCC “in relation to enhancing international cooperation related to the role of trade in this regard.”

The inclusion of the WTO and other UN trade bodies within the UNFCCC, and the emphasis on trade, specifically unilateral measures, as a climate solution, firmly legitimised CBAM within UN policy.

If the polluter pays, what’s the problem?

In the European Commission’s words, CBAM is a “fair price” for carbon. For the EU, this ‘fair price’ is set to increase its annual budget by an estimated 2%, raising approximately £1.8 billion in annual revenue by 2030.

The US’s fees will account for an estimated £261 to £347 million of this revenue, according to a report by thinktank Sandbag.

So, who pays for the rest?

According to a 2022 report by the LSE, which used several modelling approaches and priced carbon at €87/tonne, CBAM could reduce Africa’s GDP by as much as 0.91% ($25 billion at 2021 levels).

The impact on African countries, which is home to 33 of the world’s 46 least developed countries (LDCs), would be larger as a share of GDP than on any other region globally. The EU currently accounts for 26% of fertiliser, 16% of iron and steel, 12% of aluminium, and 12% of Africa’s cement exports.

During COP30, developing country parties, including blocs such as the G77 and China and the LDCs, raised concerns about the potential impact of UTMs.

In discussions at COP30, one developing country delegate noted, “In the regime we’ve created that entrenches common but differentiated responsibility, a single standard is concerning. We are told that if you want to trade, you have to meet this standard at a rate that we are unable to meet.”

Developing countries, particularly LDCs, face a unique challenge, as they lack the investment and resources to decarbonise industries heavily reliant on EU trade.

According to LSE’s report, CBAM impacts Africa’s LDCs, particularly The Gambia and Mozambique, the hardest. The research forecasts that 11 of Africa’s LDCs would experience a drop in GDP from 1.5% to as much as 8.4%. For comparison, the US is expected to experience a decline of less than 0.07% in GDP.

Perhaps the most essential part of this is to quantify absolute carbon emissions. In 2024, Europe produced 4.88 billion tonnes of carbon emissions, while Africa produced just 1.5 billion tonnes, despite having a population twice as large. The differential between the continents is stark, even when ignoring Europe’s historical emissions.

The effect is that the EU is making a profit off of CBAM, while developing countries, those most exposed to the impacts of climate change and the least responsible for it, are paying the price.

Re-inventing the wheel

Perhaps, on the surface, bridging the ‘nexus’ between climate and trade at COP conferences appears to be an innovative measure to incorporate real-world issues. But the truth is more complicated. Actions taken by the EU and UK at the latest COP summit have legitimised restrictive trade barriers in the name of global decarbonisation.

A delegate from Uruguay vocalised the prevailing sentiment among developing nations at COP30, including India, Egypt, the African Group, and the Alliance of Small Island Developing States (AOSIS): “With regard to Unilateral Trade Measures, we reiterate the position that climate change cannot be used as an excuse to impose restrictive development measures.”

If the policy truly strove to encourage global decarbonisation, it would incorporate a mechanism to reinvest CBAM profits into decarbonisation in developing countries.

—

As it stands, there is no discussion on bringing those resources back to developing countries.

Despite the outcry, Unilateral Trade Measures, such as CBAM, are officially on the COP agenda and seem set to stay there. For now, CBAM will continue to protect European businesses while transferring wealth out of Africa and other developing states.

Now, where have we heard that before?