-

The India–EU free trade agreement creates the world’s largest bilateral trade zone, slashing tariffs on most goods and aiming to double EU exports to India by 2032.

-

The deal places strong emphasis on SMEs by reducing regulatory and tariff barriers, improving trade facilitation, and helping smaller firms integrate into global supply and commodity chains.

-

While boosting trade stability, the agreement leaves the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism untouched, making carbon accounting and green production central to future India–EU competitiveness.

On Tuesday, 27 January, India and the European Union (EU) signed a pivotal free trade deal that will cut up to €4 billion in tariffs on EU exports and eliminate them for many industrial products. The EU, in return, will reduce 99.5% of its cumulative tariff lines on goods imported from India.

The deal has created the world’s largest free trade zone of nearly two billion people, making it the biggest bilateral trade agreement ever seen. The EU expects to gain complete access to the Indian market and the European Commission projects EU exports to India to double by 2032.

Machinery and electrical equipment, which make up the largest EU export category to India (worth €16.3 billion in 2024), currently face tariffs up to 44%. This is to be largely eliminated over the next five to 10 years.

Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, has notably described the agreement as the “mother of all trade deals”, a sentiment echoed by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s praise for the “biggest trade deal in history.”

In spite of a 50% tariff on Indian imports from the US, India is expected to become the third-largest in the world within the next three years, thanks in part to trade deals such as that with the EU.

The EU has also lately been on the receiving end of tariff turbulence, as US President Donald Trump threatened to apply 35% tariffs to countries that challenge his ambitions to take over Greenland.

Both India and the EU have recently signed other trade agreements as well, with the EU finalising a free trade deal with South American trade bloc Mercosur just last week, and India slashing tariffs with the UK back in May 2025.

However, this India-EU deal wasn’t purely reactive to tariff threats: it has been in the making for nearly two decades, with negotiations gaining momentum in the past six months, amid urgency for both sides to diversify their export markets.

The deal must still be ratified by EU member states, the European parliament, and the Indian cabinet before it comes into in effect.

What this means for SME financing

According to a 2021 briefing by the European Parliament, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are the “backbone of the European Union and the engines of innovation, economic growth, and job creation,” representing approximately 99% of all EU businesses, half of the EU’s GDP, and employing around 100 million people.

SMEs make up a significant portion of India’s economy as well. There are estimated to be over 42 million SMEs in India, employing about 40% of the country’s workforce. These aren’t empty statistics; the growth of SMEs constitutes an integral part of any free trade agreement (FTA).

Thereby, as per the recent deal, both parties will establish official SME contact points, designed to guide them through the legal intricacies of the FTA. While they haven’t disclosed what exactly these contact points will provide yet, SME support through FTAs tends to involve cooperation and trade facilitation.

Cooperation includes the sharing of information, especially when it comes to regulation. Although regulatory barriers are expected to ease with the deal, the EU is infamous for being stringent, often seen as setting the global standard for regulation, while simultaneously making it more difficult for external actors to access their market. Allowing Indian SMEs to enter the European market is likely to involve increased communication and transparency when it comes to compliance.

For many SMEs expanding globally, transactions are largely conducted through electronic commerce (e-commerce), which allows companies to enter new markets. But comes with its own challenges, like the application of the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) Agreement on Global Commerce, electronic authentication requirements, and domestic regulation hurdles.

Regional trade agreements (RTA) have taken innovative approaches toward these issues, centred on placing temporary holds on customs duties, transparency intensification, and improved cooperation.

As outlined by the European Parliament briefing, “FTAs stipulate regulations on trade facilitation.” There are particular regulations foregrounded for SMEs, which increases efficiency when it comes to customs. While specific regulatory provisions differ, they ultimately aim to reduce costs.

For instance, the EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA), established in 2019, had a separate chapter dedicated to SMEs. This chapter ensured both sides provide previously agreed-upon information on market access on a publicly visible website, outlining the variety of customs and intellectual property rights (IPR) legislation that SMEs must navigate, alongside a database showing information on tariffs. As thorough an approach can be expected for the EU-India FTA, making it easier and less costly for banks to provide financing for SMEs.

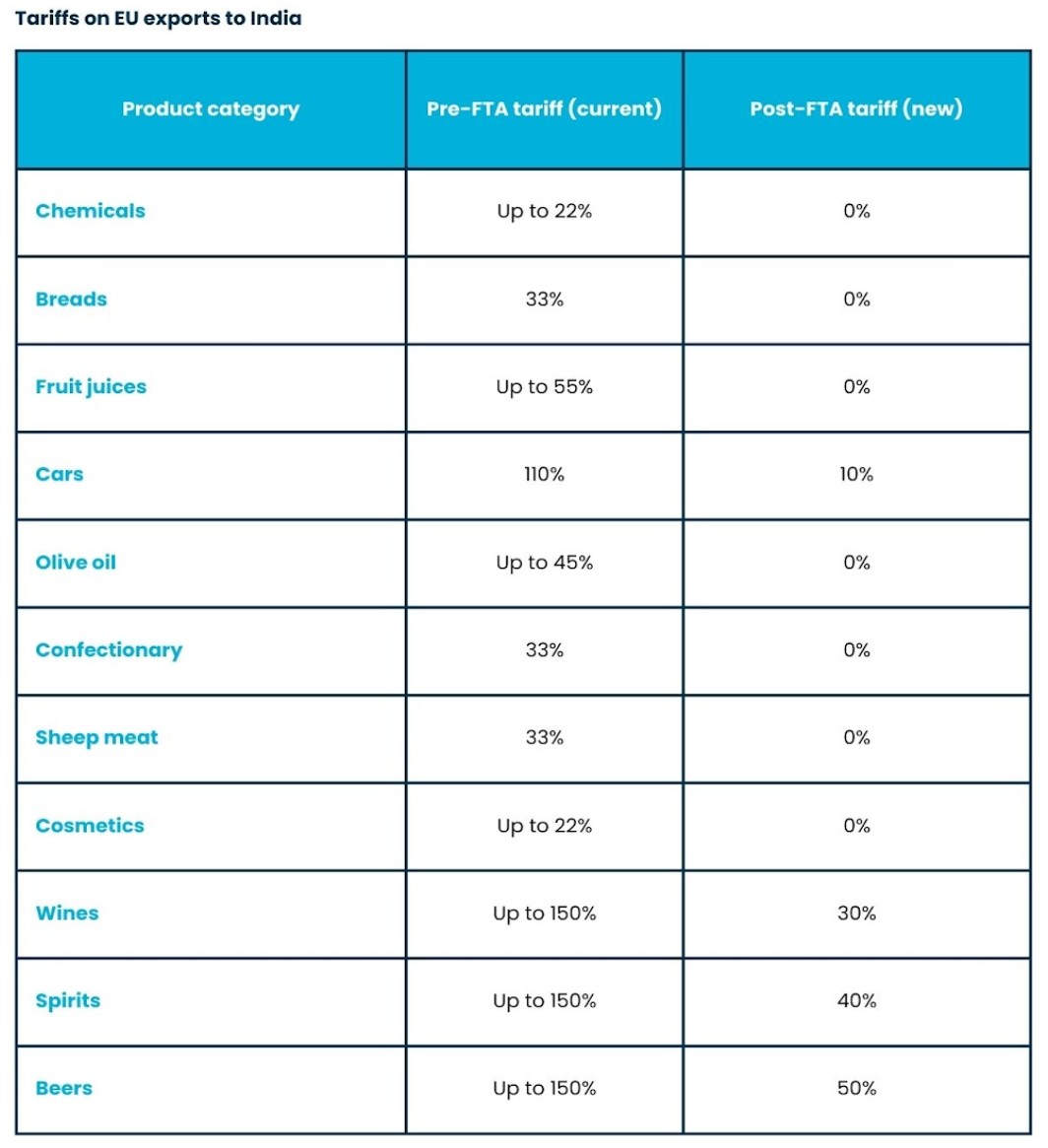

It’s also important to note that for SME in specific niches, the cost of market entry will plummet. For instance, tariffs on EU wines, which previously sat at a substantial 150%, will drop to 20-30%. Similarly, Indian textile, leather, jewellery, and footwear firms will also gain complete access to the EU market, as most tariffs will be lifted. This will grant Indian manufacturers a considerable headstart when competing with other Asian manufacturers.

Exporters will now be able to use a statement of origin to self-certify their goods, skipping over the previous bureaucratic nightmare of obtaining government-stamped certificates for every shipment.

This increased access and support for small businesses is also likely to lead to long-term relationships between Indian and European buyers and sellers, while allowing small businesses the opportunity to integrate into global supply chains, rather than operating through one-off, direct trade.

Strategic commodity cuts and stable supply chains

Commodity chains, which supply basic raw materials and agricultural products, can also expect to be impacted by the India-EU FTA. The deal has come at a critical moment, serving as a ‘supply chain reset’ for both sides to reduce their dependence on volatile trade relations with superpowers like the US and China.

However, commodity chains are particularly fragile. They often involve a wide range of disparate stakeholders, from farmers to manufacturers. The EU’s recent deal with Mercosur sparked unrest, as thousands of French and Irish farmers took to the streets to protest, fearing that the deal will batter European agriculture as low-cost foreign products dominate the market. Similarly, for both the EU and India, agriculture is a delicate sector.

India has “prudently safeguarded sensitive sectors, including dairy, cereals, poultry, soy meal, certain fruits and vegetables, balancing export growth with domestic priorities.” The EU will also maintain its current tariffs on certain products like beef, sugar, chicken meat, rice, and ethanol.

This is a varied approach, strategically carried out by both parties. By protecting certain domestic commodities, they can focus on producing and exporting those with which they have a comparative advantage, which leads to higher efficiency.

For instance, the agreement eliminates tariffs on industrial commodities like iron and steel, where the EU has leverage. A multi-faceted approach will cut costs considerably when it comes to purchasing, transporting, and importing the necessary commodities.

The FTA will also provide increased stability in sourcing, allowing both sides to operate in a predictable and transparent trade environment. Regulatory support that comes with FTAs will also ease the pressure on commodity chains.

Beyond physical goods, the new agreement eases the movement of Indian corporates across EU member states, benefiting the human side of supply chain management.

At a time when supply chain volatility appears as second nature to trade, this historic trade deal marks a move toward stability and security.

CBAM and the green transition

One of the key developments happening in tandem with this deal is widespread climate regulation. The EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) entered its full phase in January 2026, posing a major obstacle to seamless trade between India and the EU.

CBAM heavily impacts high-emission commodities like steel and aluminium, imposing a carbon levy on them when entering the EU. It requires suppliers to submit emissions data – a process unfamiliar to many suppliers outside of the EU. In the absence of emissions data, they will be subject to default values.

The India-EU deal deliberately excluded CBAM. “There is no commitment on the part of the EU to change our obligations with regard to the carbon border adjustment mechanism, or grant India more favourable treatment,” said Paula Pinho, Chief Spokesperson for the European Commission.

This indicates that although tariffs may be deducted, or even removed completely, carbon competitiveness now has an equally important effect: incentivising Indian companies to prioritise carbon accounting.

However, as a compromise, the EU committed to providing €500 million to help India build greener production methods. The agreement also has a chapter dedicated to sustainable development, focusing on environmental protection and climate change, alongside social issues.

Both the EU and India have also agreed to collaborate on implementing the Paris Agreement, the Convention on Biological Diversity, and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora.

—

Will the ‘mother of all deals’ be able to raise a competitive bilateral trade network? In its infancy it’s showing all the right vital signs, but carbon accounting, the EU’s rigidity when it comes to regulation, and stormy political alliances could portend some difficult teenage years.

However, as of now, this deal signals a move away from volatile trading partners. It reflects a desire for dependable, protected trade corridors, where trade isn’t hijacked as a political tool, but is rather seen as an enabler of mutual growth. If all goes well, this newfound alliance could unlock significant economic gains for both parties, ensure cooperation on the energy transition, and maybe even live a long, happy life.