A toxic combination of macroeconomic dispute, a global pandemic which by now we are all too familiar with and dwindling storage capacity led to negative prices for crude oil for the first time in history, and the worst performance of West Texas Intermediate (WTI) on the New York Mercantile Exchange since its futures trading opening in 1983.

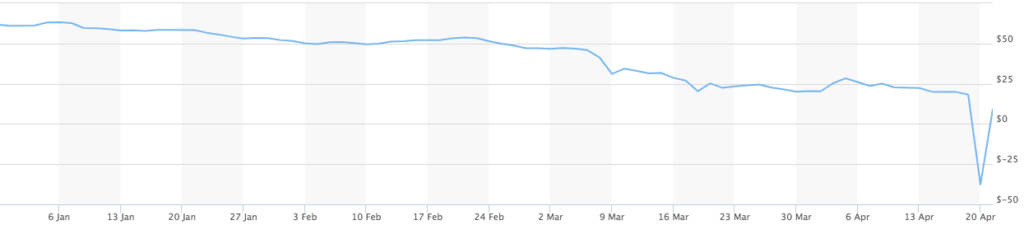

Trading at a YTD peak of around $63 a barrel in January, the commodity fell by roughly -153% to a record low of -$37.63 a barrel on Monday, marking an important moment in history that some could argue is an apt illustration of the true impact COVID-19 is having on global markets and the businesses within them.

Why is this important? Well for starters, it is the first time in history that front-month Oil contracts have fallen below zero. Essentially what this means is that holders of the commodity were paying for market players to take the contract off their hands, rather than charging a price for it as usual. This means there is effectively no demand for the oil, making it illiquid. Secondly, it is a stark reminder of just how much global activity has changed due to the global pandemic. And thirdly, it acts as a precedent for future market activity, further proving the word “unprecedented” truly holds little value today.

In a Nutshell

In order to gain an understanding of the collapse of WTI, it is necessary to first understand how the oil future markets actually trade. A futures contract is essentially an agreement to pay a certain price agreed now for delivery of oil at a later date. Many institutions and traders have long scrutinised the practise of trading oil without the necessary means to store it. This is how it became negative – if you own futures contracts for WTI without any storage capability, and the price is plummeting, better to pay someone $40 to take the contract (and thus, future delivery) off your hands than to organise and rent additional storage space that is already nearing max capacity.

Oil has been a hot topic amongst macroeconomic reporters and trading floors for the past few months, and volatility is not a new aspect of this market. However, what was it exactly that caused this historical crash?

Mainly it can be attributed to storage issues in the US. When a WTI contract reaches it’s expiry, the owner of the contracts has 3 choices – Sell the contract (at whatever price or cost), roll the interest over onto the next group of contracts, or let the contract expire and take physical delivery.

Whoever holds the contract at the time of expiration has to take delivery. The front month contract that crashed on Monday was set to expire on 21st April, and there was not enough capacity to store it.

Cushing Oklahoma is the home to the main price settlement and delivery port of US crude oil. It has a storage capacity of 76 million barrels, and according to Reuters stocks at Cushing have increased to almost 55 million barrels – up 50% less from than a month ago and roughly 70% of their capacity. So as the front month contract came to expiration, no one had the capacity to hold any new oil. When you combine these storage constraints with both the depleting global demand for oil as the world economy contracts due to COVID-19, and also the developing situation between Russia and Saudi Arabia, we gain a better understanding of how the main benchmark for US oil trading fell below zero.

“The May crude oil contract is going out not with a whimper, but a primal scream.”- Daniel Yergin

Negotiations

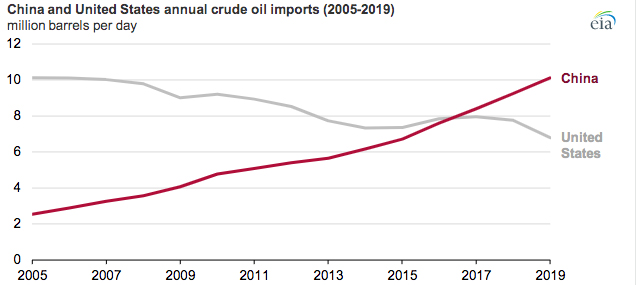

Coined by some as the “Oil War of 2020”, the starting point of Crude’s now-famous collapse can be contributed back to (you guessed it) COVID-19. Originating in China, the virus eventually led the world’s biggest economy (along with the rest of the world) to all but completely shut down for over two months. According to the US Energy Information Administration, China’s imports of Crude oil surpassed 10 million barrels per day in 2019, maintaining the status of World’s largest importer of Crude oil after surpassing the US in 2017.

As the world’s largest importer of crude went into lockdown, production companies within the nation followed suit causing massive demand depletion for the commodity. Prices for oil were already slipping, with OPEC members voluntarily reducing their production efforts in a bid to avoid a glut of Oil. Toward the end of March, OPEC members – specifically Saudi Arabia – posed a production cut which Moscow did not agree to. Saudi then retaliated with production increases aimed at damaging Russian exports through cheaper prices. And thus began the Oil war of 2020. Many discussions and disputes took place, until a production cut was eventually agreed.

OPEC+, which is the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries joined by Russia and others had come to an agreement to begin to cut oil production by 9.7 million barrels per day as of May 1st. However, as we have now seen this supply cut was not enough to support price levels of the already flooded market, and the aforementioned collapse came to fruition anyway.

On Tuesday, OPEC+ held an emergency call to discuss what could be done in the short-term, recognising actions must be taken now rather than the beginning of May. At first this sounds positive, however according to Reuters the call highlighted the ever growing divide inside the organisation. Present on the call was Algeria, Nigeria, Venezuela, Iraq and non-OPEC member nations Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan. Speaking to Reuters, two OPEC sources said “OPEC’s powerful Gulf oil producers Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, United Arab Emirates as well as Russia – the countries doing the bulk of the production cuts – did not take part”.

With Saudi Arabia and Russia holding the top two spots in global oil exporting respectively, little hope is gained from the above call. As the largest suppliers of oil – Saudi exporting $182bn or 16% of global supply, and Russia exporting $129bn or 11.4% of global supply – both their individual actions and international relations will play a significant part in the price of oil as the situation continues.

Grey Linings

Although the activities of Monday, and the above summary do depict a dark and questionable short term future for oil, it is important to recognise that the 150% decline is not applicable to all oil commodities.

Brent for example, is – at the time of writing – trading at 19.84 on 30-April contracts. Granted, this is still a heavy -36% decline from prices last week, and is also the lowest Brent has been priced since January of 2002. However, Brent will not follow WTI’s Monday pattern, and this can be attributed to the way in which the contracts are traded. WTI contracts are settled with barrels, and Brent is settled with cash meaning the price cannot fall below zero as traders will pay players to take oil off their hands, but not cash.

The Future of Oil Futures

Although industry players foresaw the price of WTI crude falling, no one expected it to turn negative. The main drivers of the price of oil are exactly what has been explored above; supply from major exporters, global demand and storage capabilities. It is these three areas that will decide the fate of Oil.

With the global pandemic beginning to ease in some countries – most notably China – world production will of course increase once more bringing with it a substantial return in the demand for oil. It is the time this will take, along with actions from OPEC, OPEC+ and global storage capabilities that will influence the short term performance of the market.

Australia

Australia Hong Kong

Hong Kong Japan

Japan Singapore

Singapore United Arab Emirates

United Arab Emirates United States

United States France

France Germany

Germany Ireland

Ireland Netherlands

Netherlands United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Comments are closed.