The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the world’s considerable dependence on Global Value Chains (GVCs). The Business 20 (B20), official voice of the global business community across G20 members, and Business at OECD recently published[1] a joint conceptual policy proposal that focuses on reducing barriers that firms in general and SMEs in particular encounter in their quest to participate in GVCs, as cross-border fragmentation and friction continue to impede the free flow of people, capital, goods and services.

The policy paper titled “GVC Passport on financial compliance, a pragmatic concept to strengthen inclusive and sustainable growth” calls on G20 nations to work towards a system envisioning a significant reduction in bureaucracy, while increasing transparency and traceability, as well as facilitate firms’ access to wider markets. This work has been led by Gianluca Riccio.

[1] At the B20 – Business at OECD – OECD joint event held on September 2nd, 2020, titled: “From crisis management-to a sustainable and inclusive recovery”.

Featuring: Gianluca Riccio (GR), Vice-Chair Finance Committee, Business at OECD

Host: Deepesh Patel (DP), Editor, Trade Finance Global

The Global Executive Forum series is a joint collaboration between Trade Finance Global and SME Finance Forum, managed by IFC.

Deepesh Patel (DP): Thank you so much for doing this with us! So let’s start with an elevator pitch from you, who are you, where are you from, and what do you do?

Gianluca Riccio (GR): I am from Lloyds Baking Group where I am Risk Development Director and have held numerous Risk and Strategy roles over the years. In addition, I am Vice-Chair of the Business at OECD (BIAC) Finance Committee and a member of the Finance and Infrastructure Taskforce at the B20, the official G20 dialogue with the business community.

Business at OECD

DP: What is the role of the Business at OECD Finance Committee, and how does this tie in to the work of the B20?

GR: Business at OECD (BIAC) is the officially recognized business voice to the OECD. Through Business at OECD, national business and employers’ federations and their members provide expertise to the OECD and governments for competitive economies, better business, and better lives. Our Finance Committee contributes private sector expertise[1] and perspectives to OECD finance-related activities, including its work to support the G20, in order to develop a strong and sustainable global financial system.

[1] Business at OECD is a consensus driven organization and therefore its Committee leadership reflects the consensus view when presenting agreed positions, rather than their own personal views or a formal representation of their employers.

Global Value Chains (GVC) and Covid-19

DP: Covid-19 has dominated the G20 Agenda, exposing the importance of Global Value Chains (GVC). Can you explain the importance of GVCs for the global economy, and what Covid-19 has taught us about them?

GR: This year, the COVID-19 pandemic and its economic and social impacts have inevitably dominated the G20 agenda. Better economic and social performance has always gone hand-in-hand with trade and market openness. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the world’s considerable interconnectedness and dependence on Global Value Chains (GVCs). Disruptions in GVCs not only knock-on an immediate negative economic impact, but can also inflict severe long-term damage to the economic fabric of societies.

DP: Why do SMEs face the most friction and disruption when it comes to access to finance and complex regulation, despite their value to global economies (as eluded to in your recent paper on Trade Finance)?

GR: It is not that SMEs face the most friction, but rather SMEs face a proportionately higher cumulative regulatory and administrative burden relative to their resources. It is true that several regulations do take into account SMEs (e.g. the SME supporting factor in capital requirements) and apply various forms of simplifications, but the challenge is the cumulative burden that weighs on smaller firms. Each policy tends to be looked at in terms of its own impacts, but firms have to manage the totality and interrelation of rules across different policies and from different regulators, and when it operates internationally the burden increases in multiples.

Policy consistency is of critical importance and needs to be achieved with a holistic view aimed at balancing Economic Growth, Financial Stability, and Productivity in order to generate growth that is genuinely sustainable[1].

[1] B20-Business at OECD (2018) – “The Productivity Challenge in Financing Inclusive and Sustainable Growth”, Joint B20-Argentina and “Business at OECD” contribution to the G20 agenda in 2018 – “Business at OECD”, Paris, September 2018. https://biac.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Business-at-OECD-B20-Financing-Sustainable-Growth2.pdf

PODCAST: $5 trillion and counting – the MSME Finance Gap

DP: Trade is a driver of sustainable economic growth, and over 80% of trade requires trade finance. Yet access to trade finance remains a challenge particularly for SMEs, in both emerging and developing economies. Why is this so?

GR: The role and further development of trade finance[1] is central to business participation in global trade activities with four-fifths of those activities – worth USD 15trn a year – underpinned by specialized loans or guarantees[2]. Yet, research indicates that 90% of cross-border trade declarations involve a broker and 75% of traders use third-party logistics providers. Escalating trade conflicts and protectionist rhetoric are taking an increasing toll on business confidence adding to uncertainty. The importance of ensuring broader access to trade financing, both traditional mechanisms and those linked to supply chain finance, underpins the discourse in our paper.

A recurring issue for example relates to the paper-intensive transactions involved in traditional trade finance where the shipment can arrive at port of destination ahead of completing the paper processing – i.e. the physical supply chain is moving more efficiently than the financial supply chain. Coming to SMEs, research indicates that they face the greatest hurdles in accessing trade finance at affordable terms. For example, the WTO estimates[3] that globally over half of trade finance requests by SMEs are rejected, compared to only 7% for multinational companies.

Key issues are that SMEs often have less collateral, guarantees and credit history compared to their larger peers. There is also a skillset gap for SMEs in both communicating their financing needs and trade finance not being sufficiently visible to them. This mainly comes from a lack of understanding as to what kind of trade finance is available, as well as how to access it.

Therefore, there is a need to work on solutions that can make the Trade Finance journey smoother, reducing the associated operating costs and those cumulative burdens that weigh on firms and are particularly heavy on SMEs relative to their smaller resources.

[1] Business at OECD (2020) – “Trade Finance: Overcoming Obstacles to Strengthen Inclusive and Sustainable Growth”– Business at OECD, Paris, January 2020. https://biac.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Business-at-OECD-on-Trade-Finance-1.pdf

[2] The Economist (2019). “Trade finance is nearing a much-needed shakeup”.

[3] World Trade Organization (WTO) “Trade finance and SMEs – Bridging the gaps in provision”, Geneva, 2016. https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/tradefinsme_e.pdf

SME Financial Inclusion from Global Value Chains

DP: Are SMEs excluded from GVCs – why so?

GR: Obviously not, SMEs form the spine of GVCs. Still, in reality services supporting trade transactions, especially financing and risk mitigation, are more easily and affordably accessible to larger companies and their Tier 1 suppliers/distributors. This results in unmet demand for trade finance, with many challenges experienced by SMEs.

Having said that, a more overarching question must still be what can be done to ensure smoother business operations in GVCs, reduce operational costs and improve the efficiency of processes? This question is valid for all firms, not just SMEs.

ICC SOS – Save Lives. Save Livelihoods. Save Our SMEs (S1 E43)

OECD-B20 Concept Paper – What is the GVC Passport on Financial Compliance?

DP: The recent Business at OECD-B20 concept paper to the G20 envisions a ‘GVC Passport on financial compliance’ – what is this, and how would it address some of the current issues small businesses face?

GR: The B20 and Business at OECD (BIAC) propose to the G20 a concept, a long-term vision, aimed at facilitating the reduction of unnecessary red tape when doing business abroad for all firms. This would happen through ensuring that financial requirements for operating in a GVC (e.g. KYC – Know Your Costumer) have to be met only once and are recognized throughout, eliminating the need for multiple re-certifications for requirements already met in one participating country.

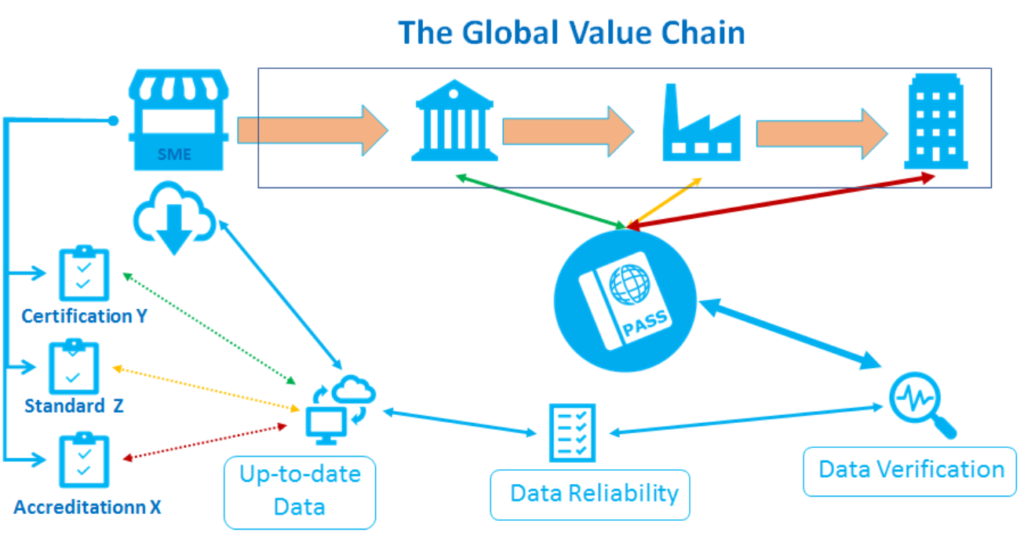

In particular, we propose to envision a “GVC Passport on financial compliance”, which could, via mutual recognition formally sanctioned by relevant authorities or appointed delegates, provide accreditation across the value chain of relevant financial requirements. A firm, incorporated in one participating country, would thereby be reciprocally acknowledged as a legitimate business entity in other participating countries; henceforth, facilitating its financial capability across the GVC by recognizing all those financial compliance and regulatory requirements already fulfilled. Hence, it would eliminate the need for multiple recertifications of the same financial requirement. The basic functioning of such a Passport is visualized in the graphic.

DP: Can you explain how the GVC Passport would work, technically?

GR: The GVC Passport is envisioned as an official (digital) document recognised within the whole GVC, across all participating countries’ borders that provides secure, verifiable and traceable financial information relating to a firm. It would capture all basic information, such as a single customer view, relating to the firm as well as confirmation of relevant financial regulatory and compliance requirements – and would come with an authoritative, trusted authenticated “stamp of approval”. The wider the list of financial requirements being fulfilled, the greater the Passport’s value. Importantly, it would not be a static certificate, but rather it would resemble a real-time application programme interface (API); a set of information and protocols always up to date.

Critical is the fact that the Passport would not only be a new document to fulfil, but rather that it compiles and recognizes certifications already received, to avoid the need to fulfil them again in the next country or next transaction. This would not avoid the firm having to comply with the rules, but it would ensure that it meets them only once, kept up-to-date to the latest validation or relevant regulation, and can be verified real-time by the authorized parties, hence avoiding firms to reapply, update or run additional bureaucratic steps.

DP: What is the role of the B20 and Business at OECD in influencing policy that will help accelerate the work needed to make this possible, and what if governments don’t wish to support the GVC Passport?

GR: The B20 is the official G20 dialogue with the business community, representing the global business community across all G20 member states and all economic sectors. Business at OECD (BIAC), the officially recognized business voice to the OECD, stands up for policies that enable businesses of all sizes to contribute to growth, economic development, and societal prosperity.

In our paper, we ask the G20 to consider the merit of the “GVC Passport” concept as a pragmatic aspirational long-term vision of enabling firms of all sizes, to participate in and take full advantage of GVCs, minimising the burdensome, and too often duplicative processes. Indeed, the very creation of something along the lines of a GVC Passport concept could never become a realistic option without a very clear enabling framework, outlining well-defined principles and minimum financial compliance requirements, which in turn can never occur without greater cross-border policy harmonisation in the first place. More specifically, what is needed is that governments work together to improve the regulatory environment consistency and administrative efficiency. Therefore, we recommend the G20 to support and prioritise proposals and policies that sustain greater cross-border policy coordination in the field of financial compliance.

Even if the GVC Passport itself would not be created in reality, it can still represent a target in order to prioritise policies that bring us towards greater cross-border (but also cross-policy) harmonisation and to identify and overcome gaps and obstacles towards this end.

Blockchain and Artificial Intelligence and the GVC Passport

DP: How can disruptive technologies such as Blockchain and Artificial Intelligence help address some of the pain points in trade and economic growth and support the GVC Passport – and why aren’t they used already?

GR: Today, online e-commerce platforms support millions of firms by enabling them to deliver goods and services to international markets with unprecedented ease; a cornerstones of efficiency gains. Blockchain make a major contribution to trade facilitations by speeding up customs procedures and trade financing and thereby taking forward the Bali Fintech agenda.

Blockchain technology is much more than a distributed storage system, built on a series of innovations in organising data and eliminating data silos, with the objective of creating trusted sources of standardised information, used and leveraged by all GVC participants. Containing a much richer dataset than that exists in any one system today, it can be used as an infrastructure for identity attestations.

Key for a “GVC Passport” to function is data verification, rather than data sharing: the very purpose of the Passport would be to confirm, i.e. verify, that the information reported is correct. A verifiable credential is cryptographically shared between peers of the GVC network to ensure underlying data is protected, without sharing the data itself. Hence, trusted servers, or certificate authorities, use such digital certificates to provide a mechanism whereby trust can be established through a chain of known or associated endorsements, complying with data privacy agreements already signed on bilateral and multilateral levels across G20, at all times.

The result would deliver a range of benefits for participants, offering faster, cheaper and safer alternatives by operating on secure databases, versus loosely connected participants of traditional processes.

ARTICLE: Morning has broken – New signals, standards, and semantics

DP: Standardisation and interoperability remain some of the biggest challenges when it comes to adoption of new technology. Amidst the huge growth of new platforms in this space, we’ve seen a lot of digital islands created, often in siloes. Will the GVC address these challenges?

GR: The Passport could help break silos by systematically gathering data and thus supporting both lending and public administration for example for tax purposes, making compliance more consistent, simpler, and less costly, as well as increasing transparency and very importantly their “traceability”. In the Trade Finance space, it could support firms, suppliers and public administrations to raise efficiencies such as netting payments, hence improving timeliness of payments, a long-standing low hanging fruit.

Critical is data quality and its granularity, and hence its reliability. Data needs to be up-to-date, possibly in real time, and offer a degree of granularity, which allows it to meet the widest possible set of requirements.

How to foster job creation, financial inclusion and economic growth

DP: How can public-private partnerships like this foster job creation, financial inclusion and economic growth?

A key ingredient is having adequate cooperation between the private and public sector. The GVC Passport as an official document could gain legitimacy only with formal public endorsement, through the appropriate authorities or those appointed / delegated by them, including Banks for example.

Intergovernmental recognition is obviously key for the GVC Passport to gain both legitimacy and operating efficacy. Nonetheless, all actors should take action, rather than only focus, or wait, on the measures to be taken by governments and public entities; in fact, progress in the right direction can also be made by the private sector autonomously. For instance, many corporate participants have already opted to simplify trade administration procedures, integrating aspects of transaction processing with freight forwarders, government bodies and document preparers, and many banks have been incentivising corporate adoption of digital solutions.

Australia

Australia Hong Kong

Hong Kong Japan

Japan Singapore

Singapore United Arab Emirates

United Arab Emirates United States

United States France

France Germany

Germany Ireland

Ireland Netherlands

Netherlands United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Comments are closed.